In October, 2016, Hollywood is set to release “Middle School: The Worst Years of my Life” –a movie based on James Patterson’s bestselling book series. As the Hollywood Reporter explains, Patterson’s series chronicles Rafe Khatchadorian's “tumultuous days as a student at Hills Village Middle School where he must use all of his wits to battle bullies, hormones and a tyrannical principal.”

It’s true that middle school has a terrible reputation. But is middle school really nothing but tumult, bullies, hormones, and oppressive administrators?

The trouble with typecasting

When it comes to young adolescents in schools, Americans seem determined to perpetuate a narrative of hormones and horror. In her book Operating Instructions, writer Anne Lamott described her worst fear as she anticipated the birth of her son: the knowledge that “he or she is eventually going to have to go through the seventh and eighth grades.” Research, too, has found that more than half of new middle-school teachers thought the statement “middle school students can be appropriately described as ‘hormones with feet’” was true.

Like Patterson’s book series, popular culture and the media play a pivotal role in shaping and reinforcing dark visions of the middle school years. Several years ago, Time magazine ran a special issue titled “Being 13” that featured a sullen, ipod engrossed teenager on its cover and a lead story titled “Is middle school bad for kids?” A few years later, the New York Times published a series of articles focused on the middle school years with bleak titles like “Middle school manages distractions of adolescence,” and labeled middle school an “educational black hole.”

With descriptions like these, it’s hard to see past the roles in which young adolescents have been cast.

In search of a new role: the thinking middle schooler

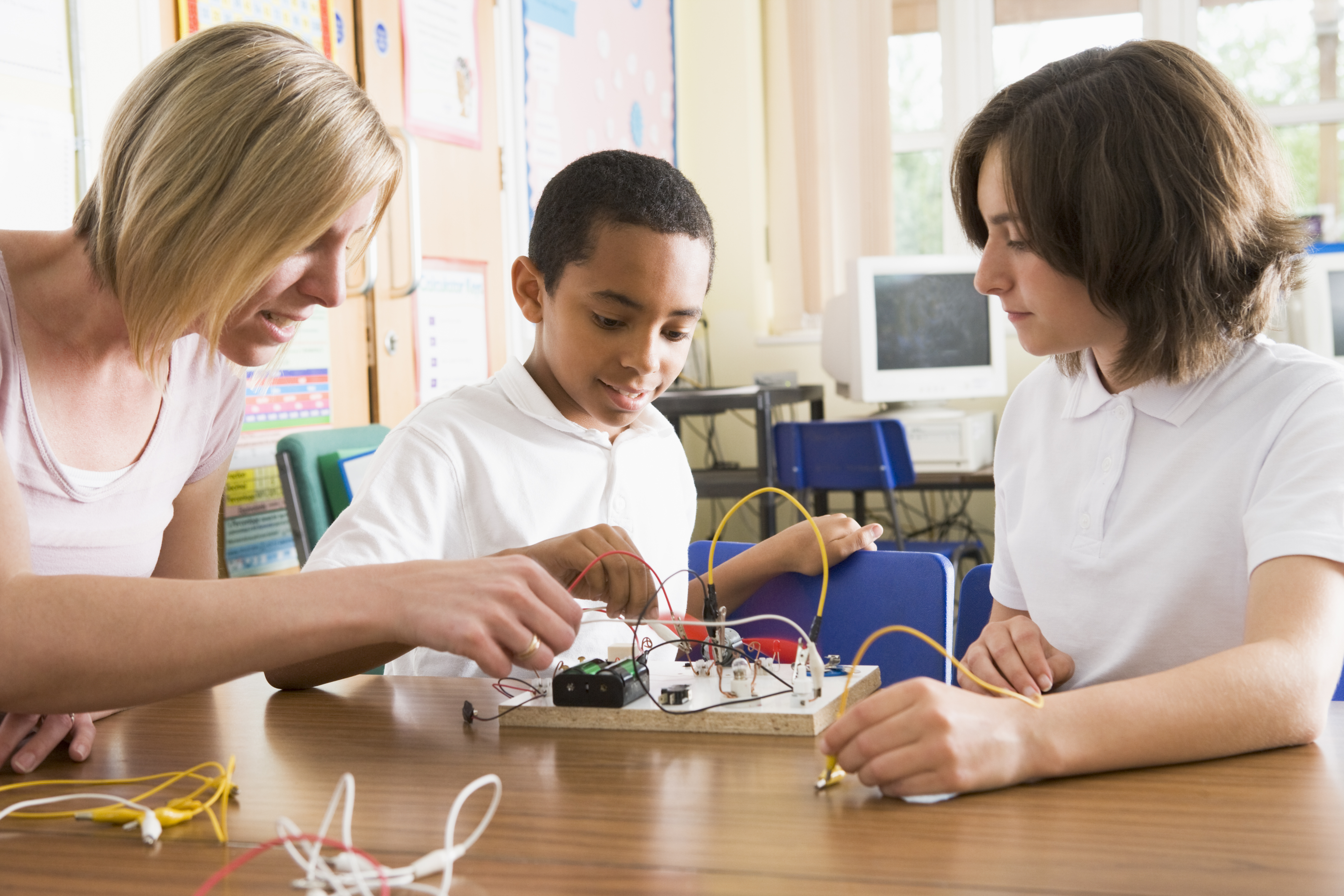

Yet while it’s true that young adolescents are navigating profound and often complex changes—new bodies, new brain capabilities, and new social realms—middle schools can be constructive, creative, happy places. When there are teachers who understand young adolescents and are prepared to teach them, smaller schools and classes that facilitate meaningful relationships, and an intellectually challenging, engaging, and relevant curriculum, middle school can be some of the most inspiring and enlightening years of a young person’s—or teacher’s—life.

In fact, because middle school students are at a time in their lives when they are developing values and gaining new ways of thinking, it is a particularly rich time to explore complex issues with them. Author and educator James Beane notes, “Those who really listen to early adolescents know that at both personal and social levels many are concerned about the environment, prejudice, injustice, poverty, hunger, war, politics, violence and the threat these issues pose to the future of our world.” A middle school teacher once said to me:

I think the hardest thing that middle schoolers face, in terms of getting in the way of what they’re capable of, is underestimating their ability. I think that middle schoolers are capable of pretty much anything they put their minds to…

In my own experience as a middle grades social studies teacher, I saw young adolescents’ thoughtfulness, curiosity, and engagement first hand. In a mock Constitutional debate, my sixth graders crafted sophisticated arguments and deliberated passionately with one another over the Federalist and Anti-Federalist positions. In the 2000 presidential election, my seventh graders proudly hosted a school-wide mock election after researching candidates’ positions on issues and articulating their own informed choices. Following the September 11th attacks, my eighth graders begged to learn more about Islam, terrorism, and Afghanistan, and together, we held challenging conversations about racial profiling.

To be sure, from an adult vantage point, young adolescents can sometimes be perplexing. At one moment, they may exhibit sophisticated, higher-order thinking and ask profound, important questions: “Why did people allow slavery?” “Why is there so much conflict between the Israelis and Palestinians?” Yet in the next breath, they ask basic, concrete questions that appear incongruous with their previous thinking: Can we use purple pen? Is this size paper okay? They often seem to possess boundless energy: they make unnecessary trips to the pencil sharpener just to move their restless legs. And, their physical development often appears out of sync with their cognitive and emotional capabilities. A girl who has reached her adult height and development may still be attached to her childhood toys.

Young adolescents are growing and learning, and they need a balance of guidance and independence. They need clear, concrete instructions to make complex ideas accessible. And they need explicit instruction in and modeling of skills adults may take for granted: how to organize a notebook and strategies for taking notes. Yet when teachers provide these supports—and show warmth, a sense of humor, and appreciation for young adolescents’ enigmatic qualities—there are rich opportunities to capitalize on young adolescents’ intellect and curiosity.

Making room to play

Another way to help young adolescents break free from the Hollywood stereotypes and practice more productive roles is to give them chances to play. Play has gotten deserved press in recent months for its role in fostering crucial social-emotional and cognitive skills and cultivating creativity and imagination in the early childhood years, in adulthood, and even among Google employees. Allowing people to play means offering choice in their pursuits, letting them self-direct their learning and exploration, allowing them to engage in imaginative creation, and do all these things in a non-stressed state of interest and joy. Young adolescents, too, need time to play, and they need time to play in school.

In sixth, seventh, and eighth grade classrooms I have observed, I’ve seen young adolescents joyfully engaged in developing governments for imaginary countries, researching and preparing “survival kits” for different climates, creating board games to review important content they had learned, and “travelling to Afghanistan” in a game of physical geography on the playground. In each of these classroom exercises, students were allowed to make choices about what they wanted to learn, had opportunities to try on adult roles, were able to develop imaginative physical and mental creations, and importantly, enjoyed the process of learning.

Across the classrooms where teachers gave students these opportunities, the young adolescents were happy and interested in their work. One said, “I have had one of the best school years because of this class.” Another seventh grader researched Ancient Egyptian mummification and showcased his learning in a creation he titled “Mummy monthly,” a clever magazine complete with cartoons and a reader quiz that asked, “Is your mommy a mummy?” His teacher explained that, “this is a kid who we can hardly get to pick up a pencil.”

Giving students occasions to learn through play not only fosters creative thinking, problem solving, independence, and perseverance, but also addresses young adolescents’ developmental needs for greater independence and ownership in their learning, opportunities for physical activity and creative expression, and the ability to demonstrate competence. When classroom activities allow students to make choices relevant to their interests, direct their own learning, engage their imaginations, experiment with adult roles, and play physically, research shows that students become more motivated and interested, and they enjoy more positive school experiences.

“Middle School: The Worst Years of my Life” may become a blockbuster hit in the theaters, but it’s time for us to craft a new plotline and offer a new set of roles. Taking advantage of the ingenuity of young adolescents like Rafe Khatchadorian may be just the place to start.

Hilary Conklin is an Associate Professor of teacher education in the DePaul College of Education. Before becoming a faculty member, she taught sixth, seventh, and eighth grade social studies. At DePaul, she teaches courses in social studies and middle grades education and conducts research focused on middle grades teacher education, teacher learning, and action civics education..

Are you intrigued by the Middle School mind? DePaul College of Education's MED in Middle Grades Education is designed to prepare educators who have a passion for, understanding of, and commitment to working with young adolescents to face challenges head-on and capitalize on the exciting opportunities of these pivotal years.